Skeletá Album Art Analysis

Skeletá Album Cover by Zbigniew M. Bielak c.2025

Zbigniew M. Bielak is an artist, illustrator, architect, and metal head who has been working with Ghost on album art and set designs since the release of their second album Infestissumam. Born in 1980 in Poland, Bielak took an early interest in drawing, but abandoned it for a time to explore music before returning to work with his father as an architect. Bielak also served as an illustrator for Polish textbooks and encyclopedias, creating drawings of artifacts found at archeological sites and accurate drawings of artwork. He first began drawing album covers after showing his work to Erik Danielsson from the band WATAIN and creating the art for Lawless Darkness in 2010.[1]

Lawless Darkness Cover by Zbigniew M. Bielak c.2010

Working with Ghost, Bielak created the album art and song illustrations for Infestissumam, Meliora, PopeStar, Ceremony and Devotion, Prequelle, and Impera. Additionally, he created the stage backdrops for the Prequelle album tour and Impera album tour.[2][3] In advance of Ghost’s 2025 album Skeletá it was revealed that Bielak once again had been tapped to create the album artwork.[3]

In an interview following the lead single Satanized, the brain behind Ghost, Tobias Forge, said “Because all the subjects were sort of core-to the bone-bone-skeleton [...] hence the name Skeletá. It’s somewhat [...] of a reflection record [...] there’s slight mirroring but also very [...] fundamental themes.”[4] Promising a more introspective album dealing with universal themes like love, lust, self-deception, sadness, and hate among others, Skeletá themes will have more to do with confronting the internal, the reflection in the mirror than the external themes of empires in Impera or the plagues of Prequelle.

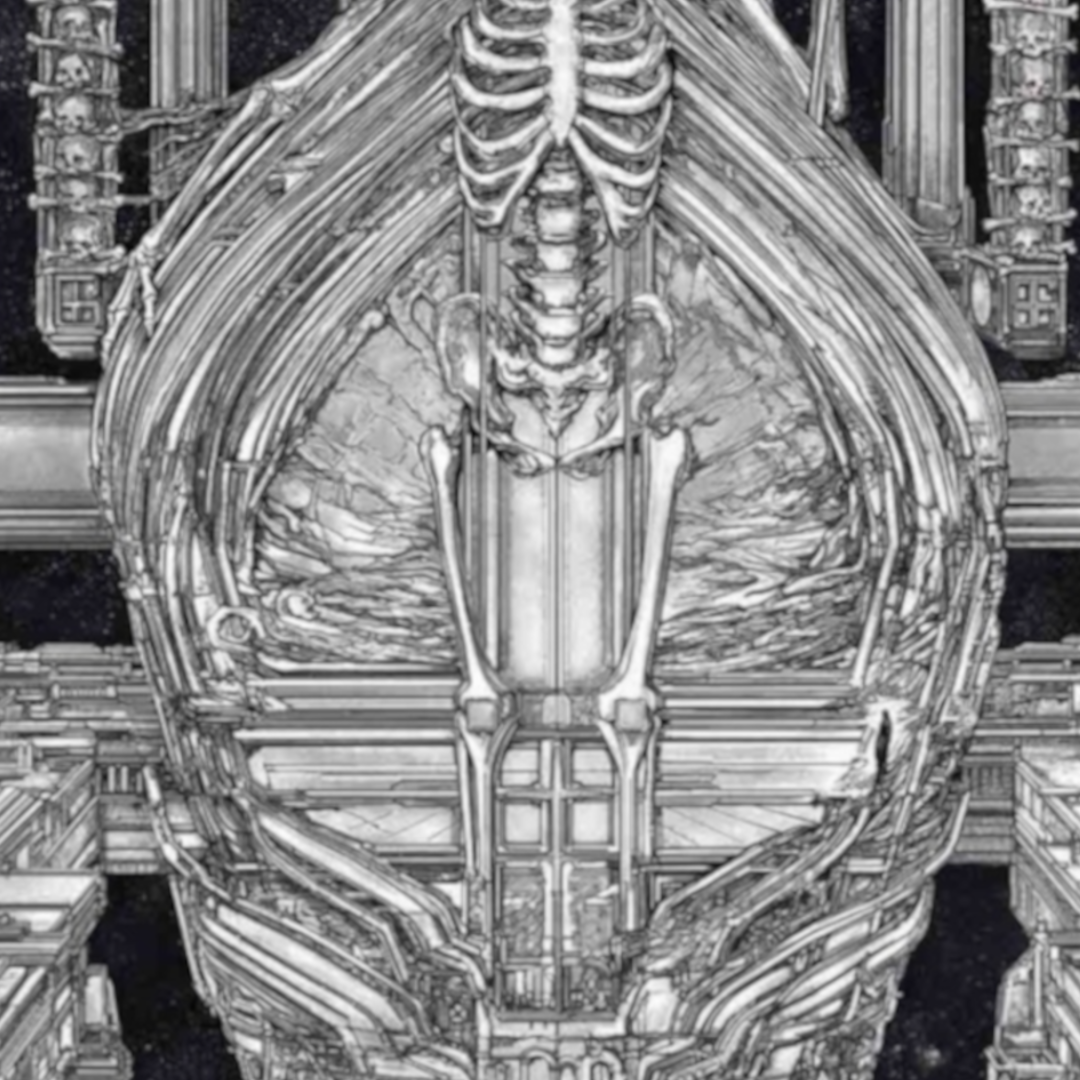

The album artwork for Skeletá, like much of Bielak’s work, incorporates intricately drawn architecture. Bielak’s cities always come off the page feeling vast and unending (and very rarely euclidean). The cities are often empty and always clean as if they’ve either just been built or were abandoned long ago. A feeling enhanced by much of the cities and buildings being devoid of life, no cars, no people, no crowded streets. Instead the architecture becomes as much of a figure in the drawing as a human in a portrait. Sometimes even literally in the case of the art for Meliora where towers and flying buttresses converge on the skyline into a face, or in the case of Skeletá the architecture melts into the central figure so that the two are indistinguishable from each other.

Meliora Album Cover by Zbigniew M. Bielak c.2015

Detail of figure in Skeletá Album Cover

In the comments on the Skeletá art on Bielak’s Facebook and Instagram, Bielak says that he took influence from Citizen Kane for the composition and 2001: A Space Odyssey for the atmosphere.[3][8]

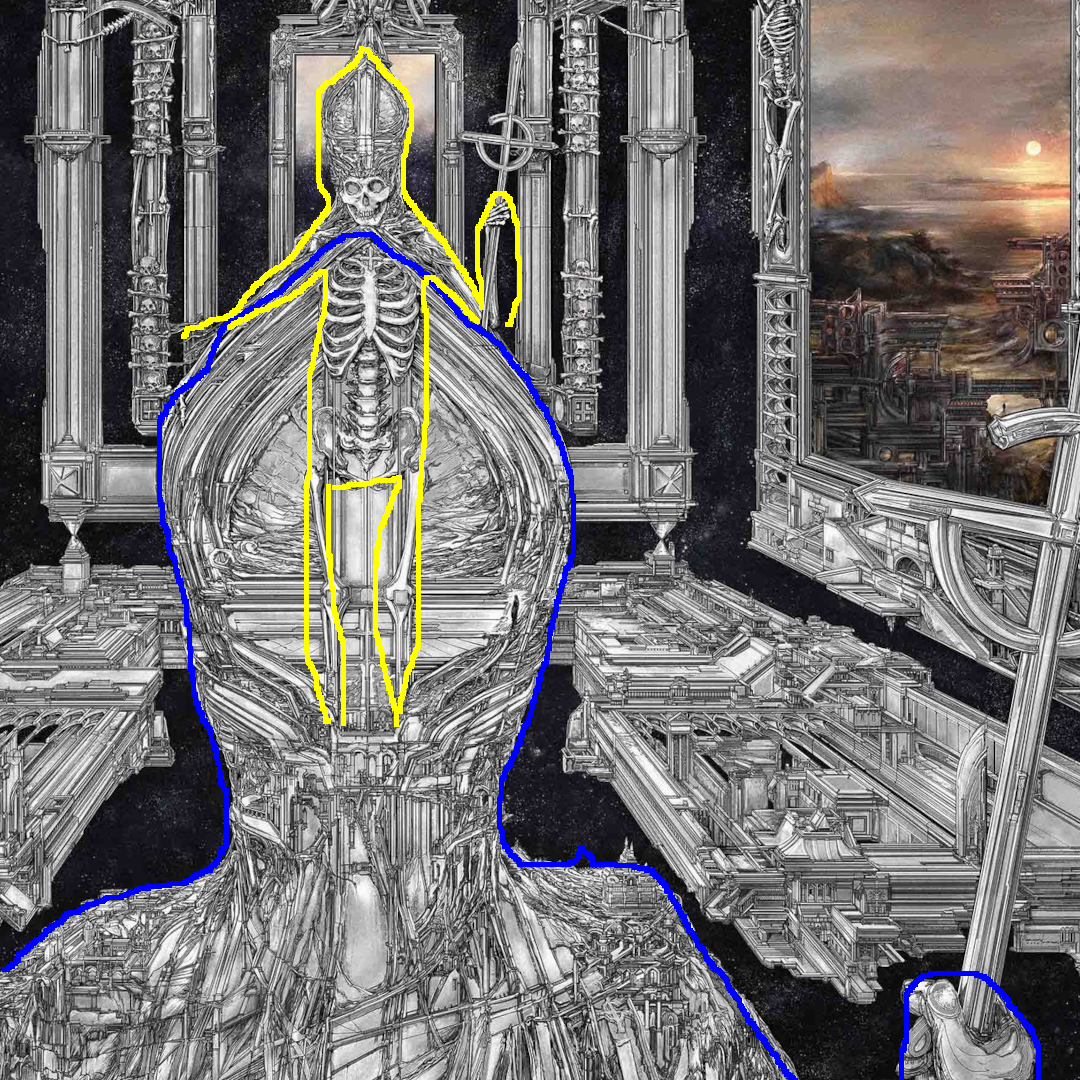

The influence of the mirror scene in Citizen Kane is evident immediately as the central figure is reflected in the mirror and down that long corridor into eternity. In the movie, Kane sees himself, alone with no one to turn to anymore after the pursuit of money and power have pushed everyone from his life. When we confront the internal, that man in the mirror, we are in conversation with ourselves and no one else. Hopefully a temporary state of solitude and not one brought about by our own greed.

Skeletá Album Cover on the left, the mirror scene from Citizen Kane on the right

The reflective mirror being put across from the viewer also follows in the tradition of portrait painting such as in the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck where not only is the back of the couple the portrait is of is visible in the round mirror behind them, but also a portrait of the artist painting them.

The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck c.1434

Or Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez, a portrait of the royal couple where instead of painting a traditional image with the king and queen visible, the artist instead depicts what they would have seen as their portrait is being painted, with the royal pair only visible in the image in a mirror on the back wall.

Las Meninas by by Diego Velázquez c.1656

This trick of perspective invites the viewer not to just see the painting, but become a part of it. Bielak has cleverly used his architecture to seep into the central figure’s main shape, pushing the figure into the background even as they are the foreground. This allows the figure’s perspective in the image to be replaced with the viewer’s own. As we gaze into Bielak’s mirror, our own visage is replaced with a skeleton. In the mirror, we confront our own internal struggles, as ever present in every human as our skeletons, laid bare upon reflection. The very bones of our being on which we have built ourselves.

In their thoughts on Citizen Kane, the commentator Renegade Cut talks about how the themes of the movie are simplistic and not that deep:

“Yeah Citizen Kane, I know not to lose my values and be a jerk to other people, but we still do. We still absolutely do. All the time. Movies with the same message will stop being made once we, as a species, get the message.”[9]

Repetition. As the reflection in the mirror repeats, so do our internal struggles. We have no better ideas on how to successfully live life than we did over 2,000 years ago. Epicurious wrote in ancient Greece that of all things in life that makes for the happiness of the whole person, the most important is the acquisition and care of friendship. Advice that is as good now as it was then. The struggles we face now are the same as we always have. Technology has changed, but we as people remain the same, struggling with the same anxieties and depressions as Throck the cavewoman did at the dawn of human consciousness.

There is comfort in knowing we are not the first to struggle, a millennia of people struggled the same before us and a millennia will after us. We are not unique, nor are we alone. Our problems are not insurmountable. We are the reflection of all the humans who mastered their turmoils of the spirit who came before us just as we will reflect the image of our victories and our losses to those who follow behind. Jane Austin may not understand a cell phone, but she certainly knows a broken heart.

And even if we don’t think of the long history of human struggles, even in our own life the same hurts will rise again and again. A careless word from our friends hurts just as much now as it did when we were young. Those vicious whispers of the mind telling us we’re unworthy, we’ll never catch up, exaggerating every flaw and shortcoming must be defeated again and again. Each time another victory comes, a lifetime of defeating that critical voice of the mind that repeats ‘You are worthless’ made weaker each time it loses the battle as you assert your will to live, to find happiness. If our lowest of low points repeat in the mirror, then so do our highs. The message repeats.

2001: A Space Odyssey, the other inspiration Bielak cites, deals with repetition as well as the 3 acts of the movie mirror each other in eternal recurrence. Each time a monolith appears, mankind takes another step forward. Kubrik was a known admirer of the philosopher Nietzche. Even using Richard Strauss’s tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra in both the beginning of the movie as the apes have their first awakening to move beyond apes and the end of the movie when the Starchild has moved beyond being human. The music which was inspired by Nietzche’s book of the same name. Nietzche offered eternal recurrence as a litmus test, posing the question:

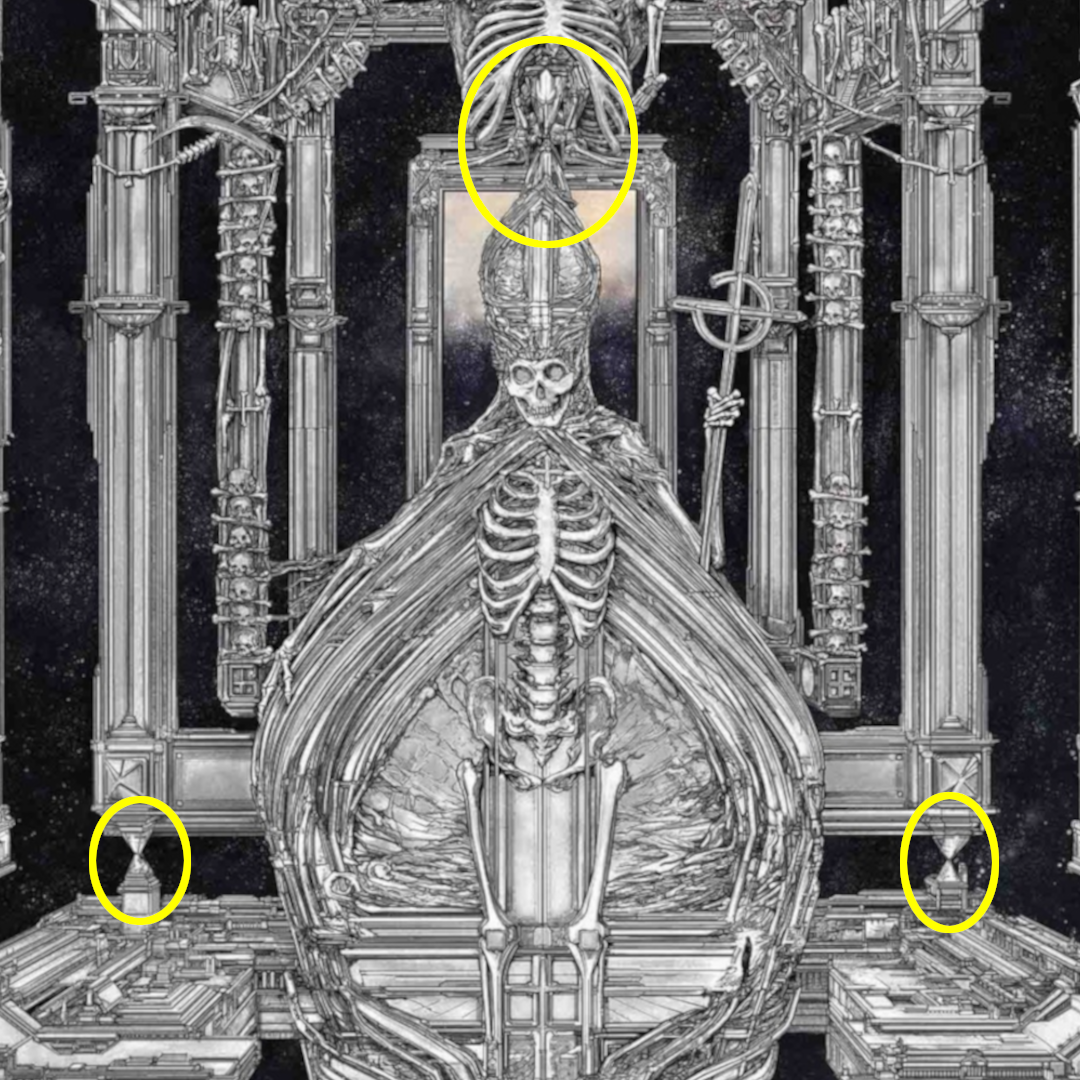

“What if some day or night a demon were to steal you loneliest loneliness and say to you: ‘This life as you now live and have lived it you will have to live once again, and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and every sigh and everything unspeakably small or great in your life must return to you, all in the same succession and sequence - even this spider and moonlight between the trees, and even this moment. I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again and you with it, speck of dust!”

“The question in each and everything, ‘Do you want this again and innumerable times again?’ would like on your actions as the heaviest weight! Or how well disposed would you have to become to yourself and to life to long for nothing more fervently than for this ultimate eternal confirmation and seal?”[The Gay Science]

When we see ourselves reflected, naked to our bones, in Bielak’s mirror, are we happy with what we see? Is every repetition of our reflection, innumerable times again and again into the distance, one that we can be satisfied with because each choice we have made has been one worth making. Or, if the repetition makes evident some flaw and bear it down on our consciousness so that it cannot be ignored? And can we find a way to change it if we can or can we find the strength to live with it?

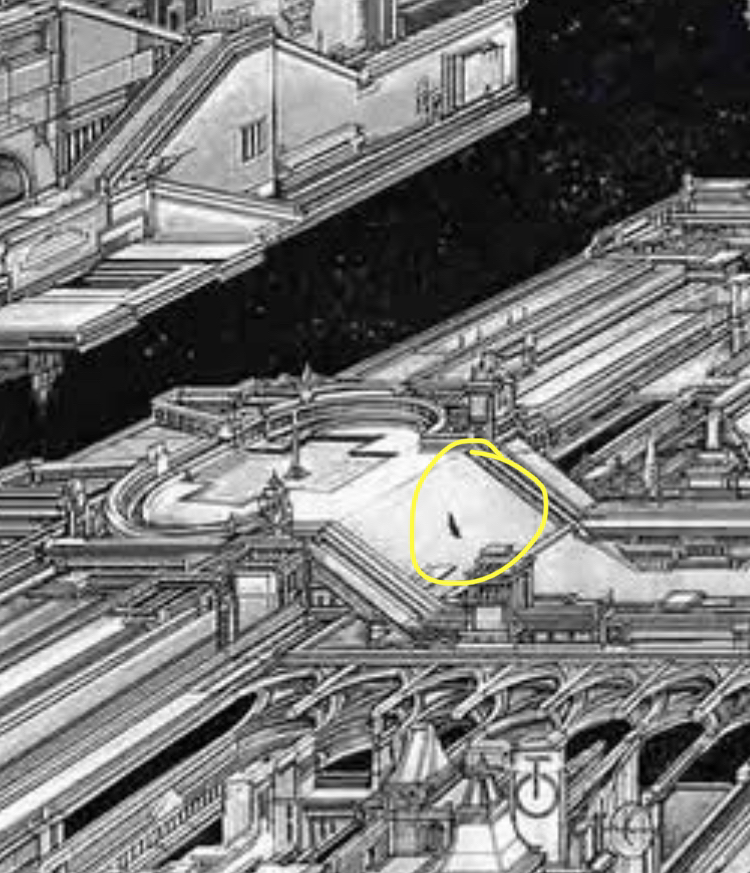

Because everything we see in the mirror, flaws and perfection are us. The reflection is separate, something we can see and confront, but it is also us. Something so beautifully illustrated by Bielak’s playing with occlusion, the reflected skeleton is further away from the viewer than the central figure being reflected and thus should appear behind the central figure. Bielak places the reflected skeleton in front of the main figure, as much a part of the main figure as the architecture that melts into their form. The skeleton is at once in front, behind, and a part of the figure. There is no escape from this reflection, we cannot turn away for it is behind us, we cannot leave it in the mirror because it is a part of us.

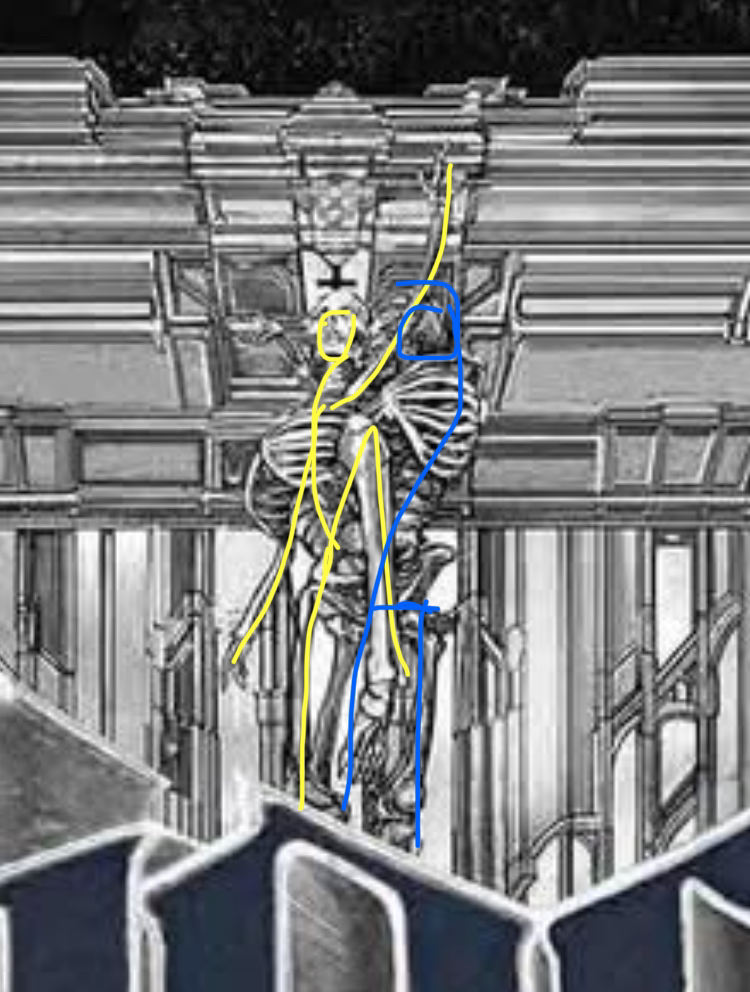

The Main figure, closest to the viewer, is outlined (poorly) in blue while the reflected skeleton, further from the viewer, is outlined (even more poorly) in yellow

Indeed, the outermost mirror is supported by hourglasses while the frame of the innermost mirror contains skeletal hands holding an hourglass. Ready to turn it over and let the sands of this moment repeat over and over again as Nietzche’s demon promised. Time ever repeating but never moving forward or backward in a way that we cannot leave in the capacity of the 3 dimensions of space, nor the 4th dimension of time. We are always Rite Here, Rite Now.

The three hourglasses I have found (so far) in the work circled in yellow

The whole scene drifts on a background of cloudy fractals dotted with white like stars bringing to mind space and its infinity. Particularly as 2001 was brought up as inspiration for this piece. There are no spatial limitations the reflections can go on as un-ending as the skeletons to be found. Even time does not constrain the scene as without the anchor of a sun, neither days nor nights can pass. We can gaze into this mirror unlimited by that which is physical, only that which our minds and our souls conjure can reach here. Free from others, but never free from ourselves.

Again, turning back to 2001, the composition of the Skeletá cover is very similar to the room Bowman enters at the end of the movie, which is sometimes described as “the most Kubrik room to have ever existed.” The room itself has odes to French NeoClassical decor that was popular during the period of Enlightenment. Bowman is brought to this place to become enlightened, to evolve past his humanity into whatever comes next.[6]

Of this scene, Kubrick has said:

“He is taken into another dimension of time and space. Into the presence of god-like entities who have transcended matter and who are now creatures of pure energy. They provide an environment for him, a human zoo, if you like. They study him. His life passes before him. He sees himself age in what seems just a matter of moments, he dies, and he’s reborn, transfigured, a superbeing.”

The central figure of Skeletá’s album art is suspended in space, outside of time, in much the same way. Often when we confront ourselves in a mirror, much of our lives passes before us too. Reliving our mistakes. Our victories. Our faults. Our virtues. Facing these things, learning from them, overcoming them, helps us evolve too. To grow past what we have been and into what we will become. To be enlightened.

Top Left: Cabinet des jeux of Louis XVI in the Palace of Versailles

Bottom Left: The final room from 2001: A Space Odyssey

Right: Skeletá Album Cover - note how the mirror occupies the same space as the Monolith

The mirror is flanked on either side by two paintings, which happen to be the only color native to the artwork. Each painting depicts a landscape that, as an American, I can only say reminds me of the Hudson River School. A philosophy of landscape paintings that came about in the Americas in the late 1800s identifiable by their sweeping vistas of nature, mountains, rivers, forests, often with a small figure painted into the foreground for scale.

Both the painting to the left and right contain a lone figure almost lost amongst the landscape. Hudson River painters would embark on adventures to find the subjects of their paintings, traveling to the remote parts of the Americas, just as Bowman adventures into a remote part of time and space, to study and make sketches and studies that they would bring back with them to make enormous paintings. Not as much to be bought and sold by collectors, but experienced for a nickel by anyone. Paintings for the people, as it were.

Left: Skeletá Left Painting detail

Right: Kaaterskill Falls by Thomas Cole c.1826

Left: Grand Manan Island, Bay of Fundy by Frederick Edwin Church c.1852

Right: Skeletá Right Painting detail

The mirror scene contains so much of one human, reflected into eternity. But it is surrounded by images of nature. The grand sweep of a mountain or the vastness of an ocean can make you realize how so very small a human is. Despite the urban legend about the Great Wall of China, no human structure is visible from space. No life lasts as long as a mountain. No human has ever actually cried an ocean of tears. Bielak’s mirror may show us as central in our own lives. The turmoil of confronting ourselves and the time spent in reflection may repeat into infinity. But what is it compared to nature? The trials of our day may seem vast when viewed from the space of our own heads, but the sun will burn long after our passions have cooled. Some infinities are bigger than others, a comforting thought as much as a despondent one.

An equal interpretation of the sweeping landscapes flanking Bielak’s mirror would be that our repeating struggles with love, hate, self-deception, lust, and all those demons that dog the mind, is as eternal as the mountains and as natural as the trees. An interpretation made stronger because the two paintings at the sides actually form a triptych, there is a third landscape depicted in the head of the central figure. The thoughts of the mind, the desires, the wants, the needs are as much a part of what is natural as the mountains, rivers, and trees we see in the painting to either side. The biggest difference being that while color and shape is defined in the outside world by the nature of reality, the colors and shapes of the interior landscape are left to us, both in it’s more impressionistic…almost completely abstract…drawing and the fact that it is to be printed on foil, meaning it is to the viewer to bring the color to the landscape of the mind. It is also, unlike the other two, devoid of buildings. Here the land is for us to build on, or not build on, as we see fit.

Detail of the center landscape in the head of the main figure

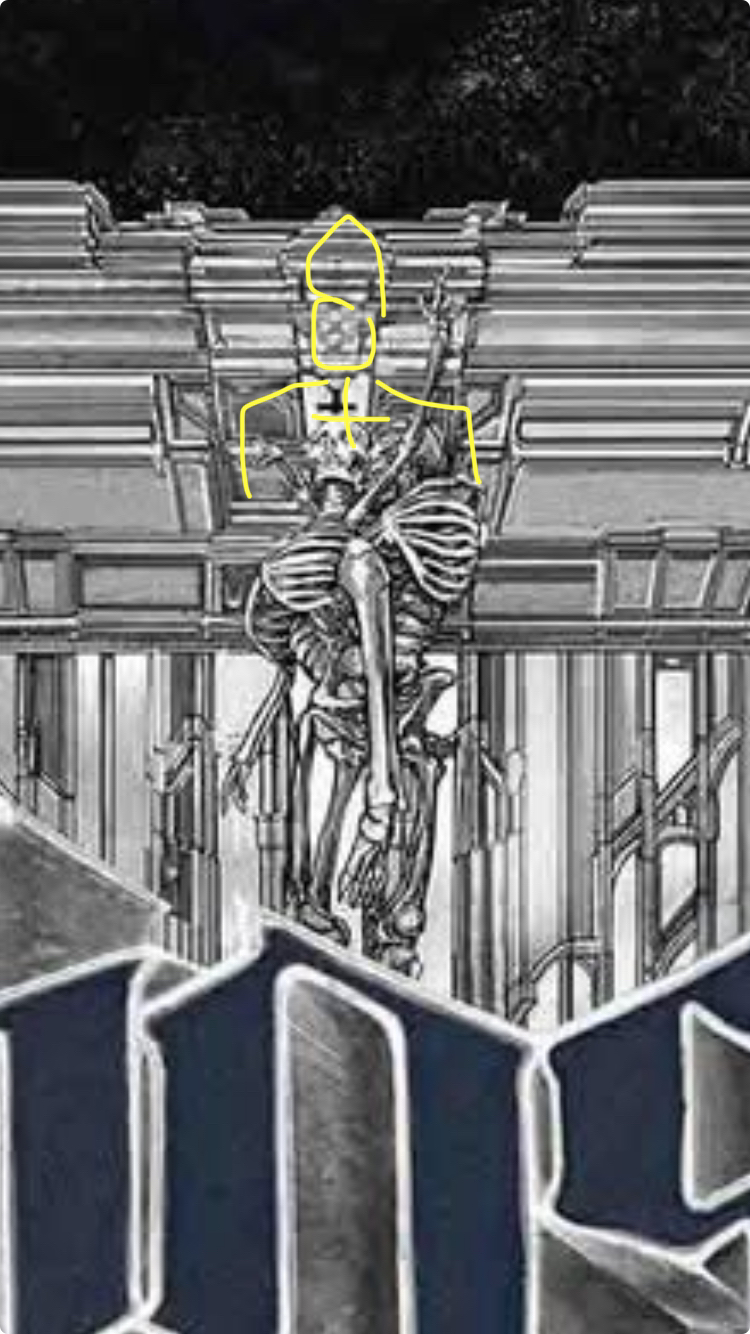

It is of note that Nietzche believed there were two things that would stop someone from being who they could become.[7] One is religion, which is evident from the plethora of crosses, but also the skeletal reflection wears religious garb, bisecting the landscape of the mind and overwhelming it with it’s monstrous presence. The second thing is nationalism. Just above the priestly skeleton is another skeleton crowning itself while caressed and attended to by smaller skeletons. A reading of them could be that this landscape of the mind is in danger of being dominated and built upon by these outside forces, stopping the growth and evolution that should take place there. To exist in peace with this landscape of the mind is to break free from these external forces, as the small figure breaks free of the gothic framing surrounding it.

Skelton in religious garb highlighted in yellow and skeleton crowning itself highlighted in blue Skeletá album cover detail

Detail of centerlandscape, bisected by the the religious skeleton and with the small figure breaking away from the frame circled in yellow

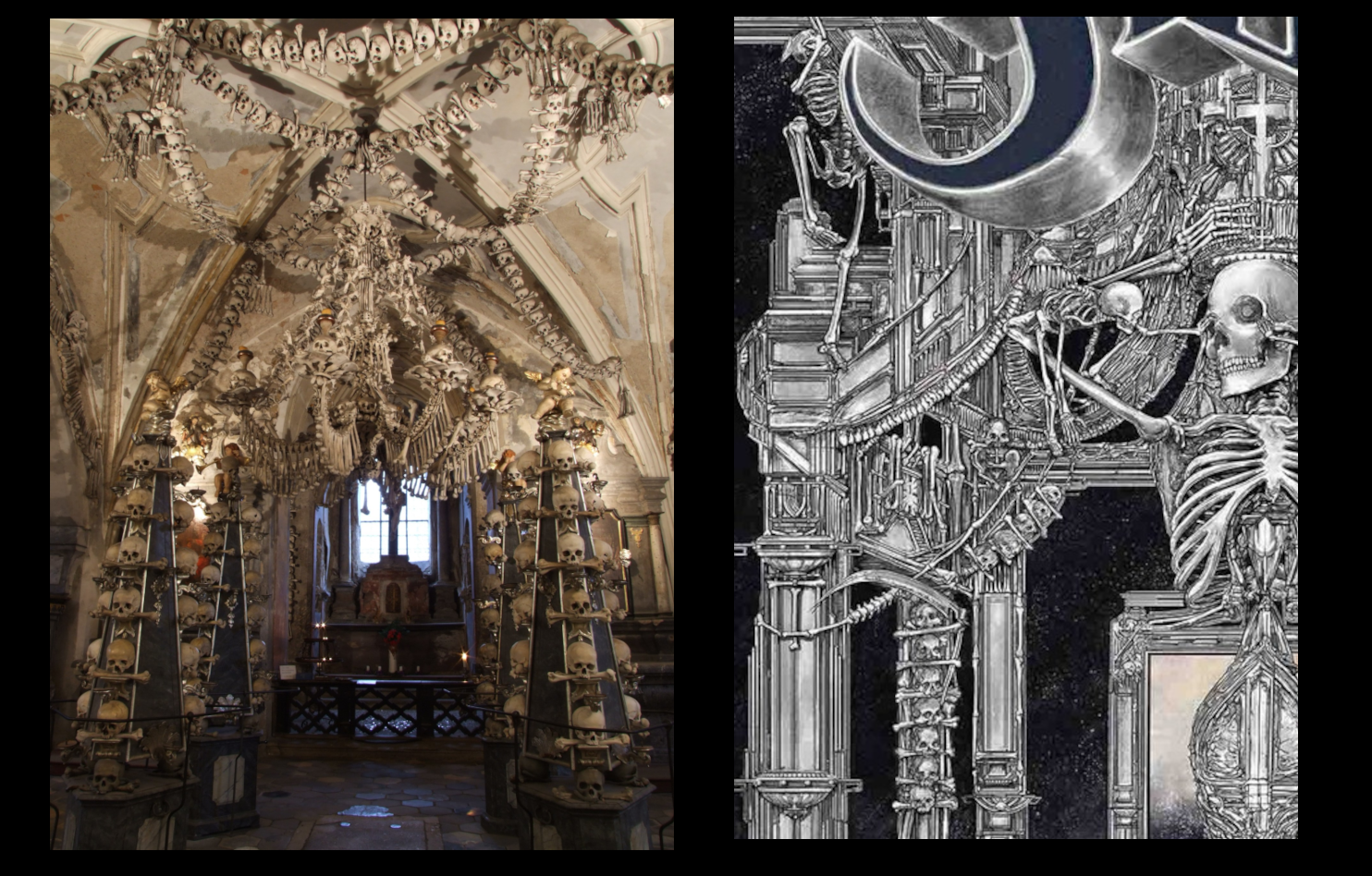

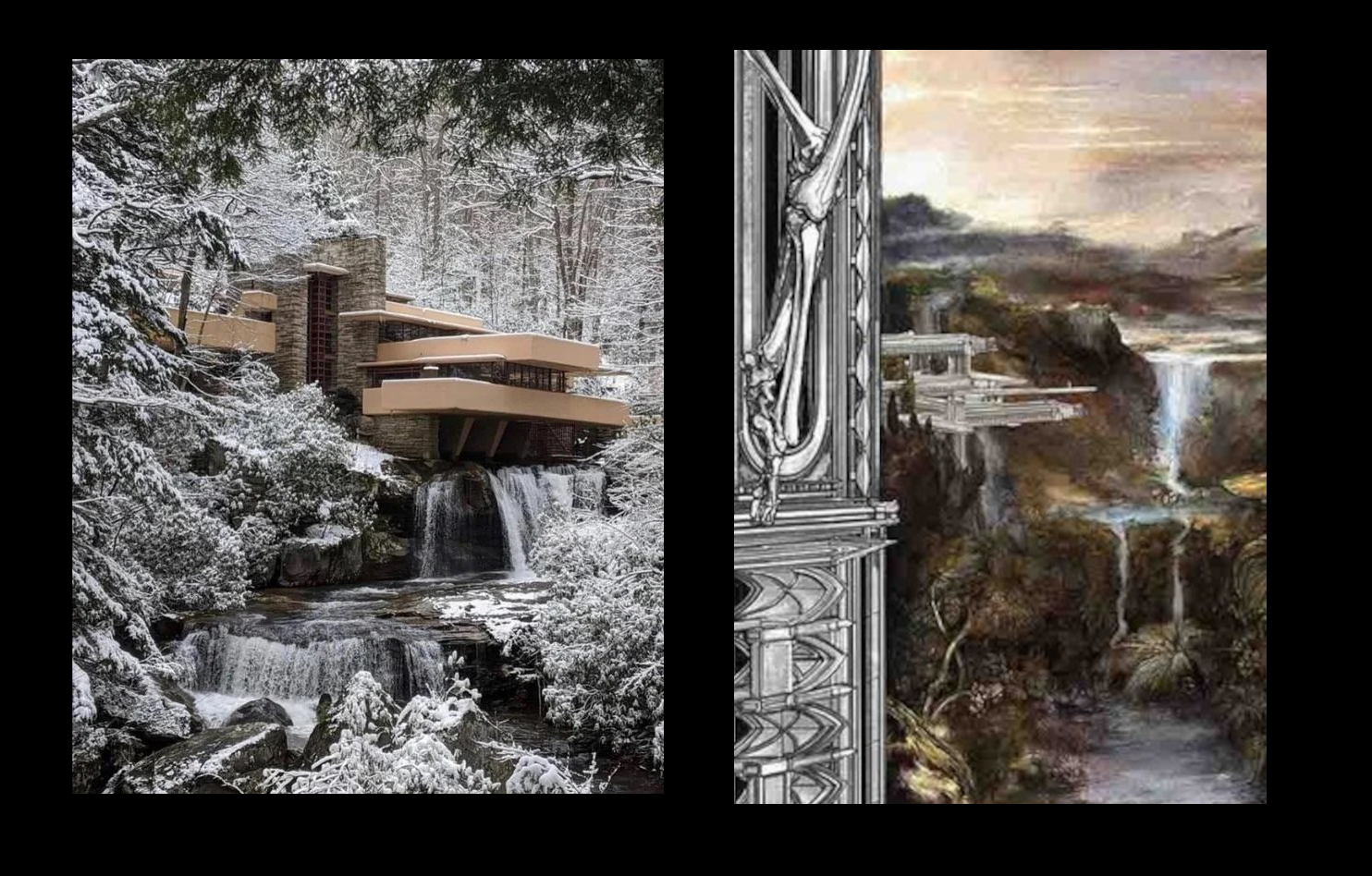

The left image shows a building and a waterfall. Likely due to my continued Americanism, I see Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. I can’t help it. You put a cantilever building near a waterfall and that’s what I’m going to see. Fallingwater is perhaps the most famous home in the United States next to the White House. This, as much as the color in the painting, stands in contrast to the architectural structures used in the black and grey portions of the image are gothic in nature (indeed bringing to the front of mind the Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic). Knowing that as an architect, Bielak would have studied different styles of building and philosophy behind them, I think significance can be derived from the two styles of architecture. Gothic architecture was utilized in churches to draw the eye up to think on the splendor of God, creating colorful, airy spaces with vaulted ceilings and stained glass. These were buildings designed to make you feel the awe of the divine, to feel supernatural. To rise above the ordinary land and impart the awe of Heaven.

Left: Sedlac Ossuary in the Czech Republic

Right: Detail of similar skeletal decoration in the Skeletá album cover

Wright, on the other hand, had a much different philosophy to his building designs. He always strove to create structures that were as much a part of the landscape as the nature around it, saying of Fallingwaters:

“I think nothing yet ever equaled the coordination, sympathetic expression of the great principal of repos. Where forest and stream and rock and all elements of structure are combined so quietly that really you listen not to any noise whatsoever, although the music of the stream is there, but you listen to Fallingwater the way you listen to the quiet of the country.”

Ghost has always been a band critical of Christianity. Nothing has changed with the first single off of Skeletá, Satanized. The lyrics tell the story of a person struggling with their desire because they feel shame as they have been told they are unholy. Even though it is a perfectly natural feeling for any human to have. Their anguish throughout the song comes from being told that they cannot have desire and be a good man, so they pray that it will be taken away from them. They are trapped and agonized by religion because they struggle against that which is natural. The central figure being consumed and surrounded by the Gothic architecture as a metaphor for being ensnared by religion it represents, while just to the left is a more tranquil scene. One where the architecture is in harmony with nature, not separate or above it. There is sunshine. There are trees. There are waterfalls. There is peace for the person who accepts that which is natural and lives in harmony with it.

Left: Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright c.1936-1937

Right: Skeletá album cover left painting detail

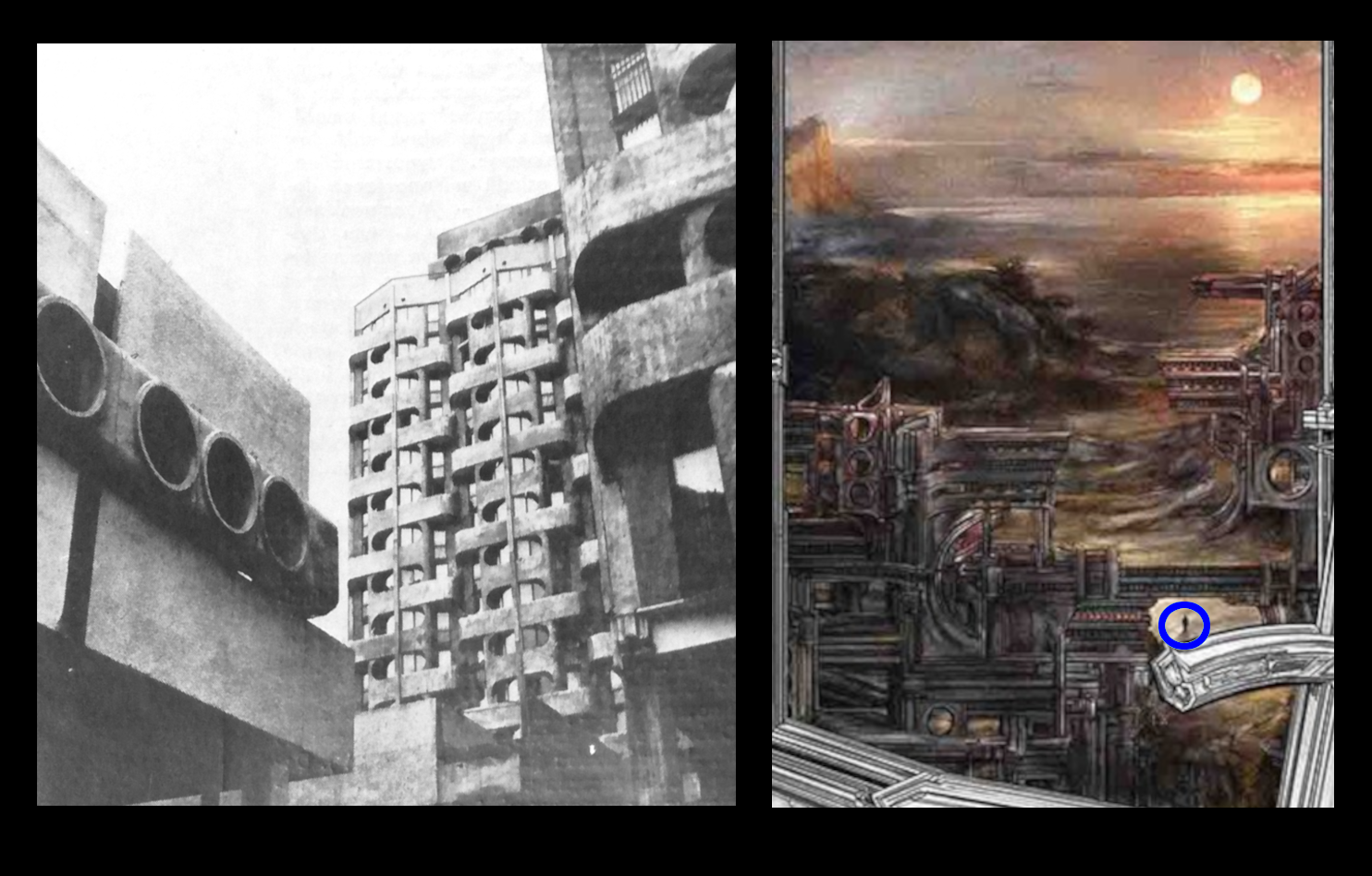

In the second landscape to the right there are more buildings. Again these are distinct from the Gothic architecture in their more contemporary design. There are round windows and the continued use of cantilevers, although this time there is no waterfall but an ocean, or perhaps a Great Lake. This time, because the buildings seem to be more like apartment complexes than family homes, I think about the Socialist Modernism time period of architecture. The most common western conception of the style is that it is grey, drab, utilitarian, and oppressive.

And, well.

Much of it is.

But.

This time period also allowed for some of the most fantastic and artful buildings to be constructed. Buildings that looked to a future that was unencumbered by the past. Inspired by what humanity is and what it might become. Buildings that took back identity for the satellite nations of the USSR. Buildings that expressed hope that the future would contain a peace that would last forever[10]. Often when scifi works create cities, they draw on these very buildings for inspiration. In this drawing, there is a small figure walking amongst the city (there may be a figure in the painting to the left, but it could also be a part of a tree, it is unclear to me in the digital version currently available).

Left: Manhattan Estate in Wrocław, Poland by Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak c1970-1973

Right: Skeletá album cover right painting building detail with figure circled in blue

Bielak included the image of a sun in both left and right paintings. Time passes here, in these worlds outside the chapel of the mirrors. Things end and begin again in cycles as the seasons, always the same, always ever changing. Unlike the central drawing, hung in the space between the stars and at the whims of an hourglass, repeating the flow of the same grains of sand over and over.

Perhaps my favorite part of this piece (although it is hard to pick one) is that the grey and white parts are to be printed on a foil, which means they will be reflective. Before I said that the paintings were the only color native to the image, but with the central figure and chapel of mirrors being reflective it means the viewer will be bringing color to this space. As if this area for self-reflection contains only what you bring to it. To interpret, or not interpret. To color or not to color. It is on the viewer. The one who looks into the mirror. To gain understanding, despair, healing, pain, peace, and all these things. What you bring to reflection is what you receive from reflection. And the fact that this art can send my mind whirring with so many thoughts and I haven’t even seen it completed yet just fills me with enough fervor of thoughts to write 3764 words on it.

Resources

- [1]High Fidelity, Interview with ZBIGNIEW BIELAK Graphic designer, illustrator, architect, metal lover, audiophile by Wojciech Pacuła (translated by Microsoft Translate so my apologies to Bielak or Pacuła for any incorrect information caused by this)

- [2]zbigniewbielak shop, Ghost artwork section

- [3]Instagram, zbigniewmbielak

- [4]YouTube, Tobias Forge Talks New Single Satanized & Upcoming Album by 93XRadio

- [5]YouTube, Citizen Kane Hall of Mirrors

- [6]YouTube, 2001:A Space Odyssey - Ending Explaing by The Take

- [7]YouTube, Was Nietzsche Woke? by Philosophy Tube

- [8]Facebook, Profile Zbigniew M. Bielak

- [9]YouTube, Citizen Kane - Renegade Cut (Revised Version) by Renegade Cut

- [10]YouTube, Soviet Architecture - Cold War DOCUMENTARY by The Cold War

Some Notes on Art Analysis

This is not intended to be the end all be all interpretation of the Skeletá album art. It is only (some of) my personal thoughts and interpretations of what I’m seeing based on my own life experiences and the few things that have been said about the album and the artwork. It is what I’m bringing to the piece and how I’m experiencing it.

It’s not the only way to experience it. I’m not prescribing it as a correct way either. Or even what Bielak was thinking as he made the piece. Certainly he can do that himself and does not need me jamming 3000 words in his mouth like I’m trying to make some kind of art foie gras. These are my thoughts and interpretations, some of them may line up with the original artistic intention some of them might be wholly my creation.

I fully embrace the idea that art is not complete without a viewer. However you view the art completes it and makes whatever you’re seeing and feeling as correct. That goes for paintings, music, books, and essays and I hope that by sharing a detailed breakdown of what I’m feeling it might help you interpret what you’re feeling or even see parts in a new light.

Other Stuff I Noticed that I Think is Cool but Have No Thoughts About

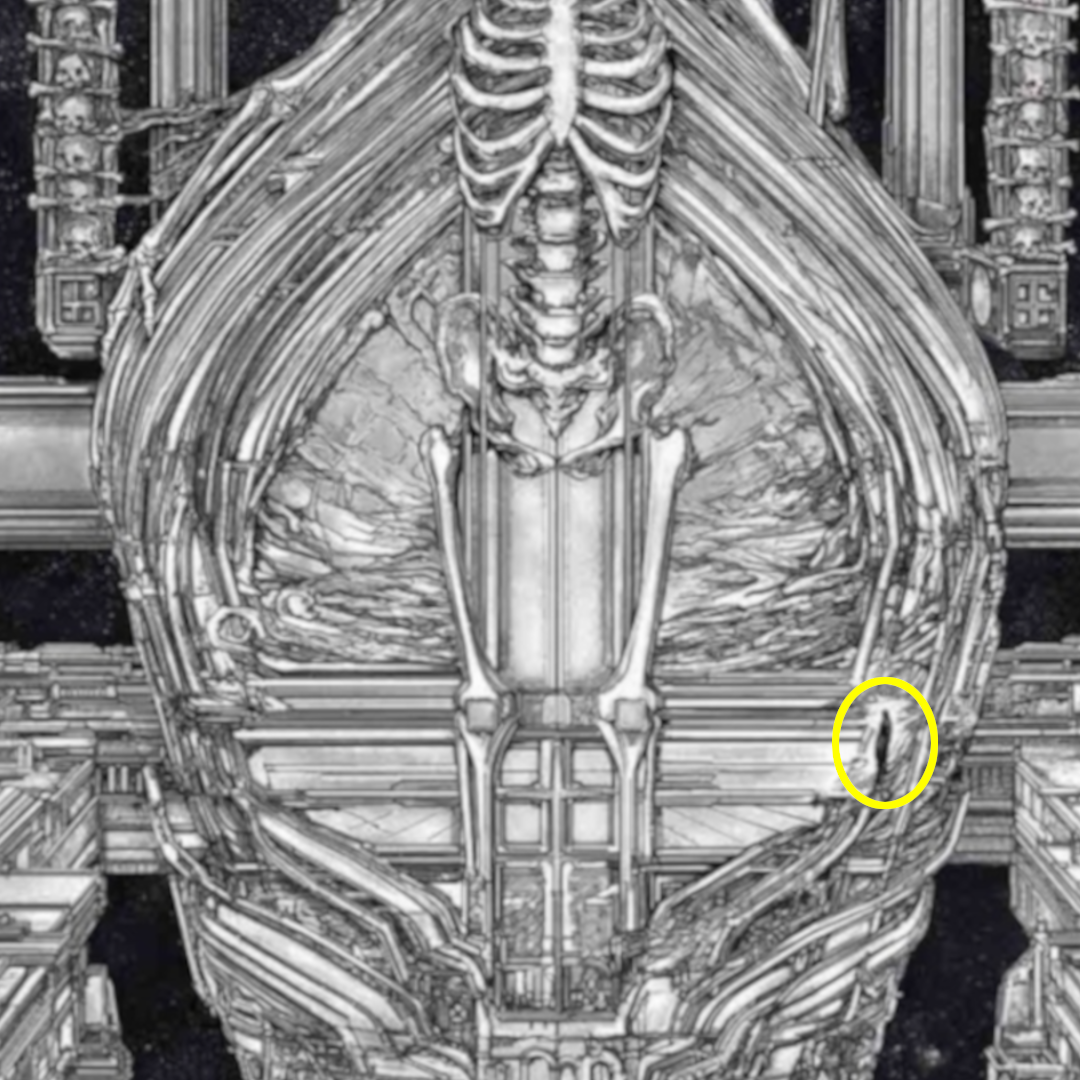

There is a small figure that seems to be climbing these steps.

One of my friends thought this might have been an AI generation when the cover got released before we had offical sources confirming it because this just looks like a pile of bad anatomy. It's acutally two skeletons having sex...or boneing hehehe

This one could just be me seeing stuff, but it looks like there's a littl priest dude who is made out of the woodwork here